(CLAIR – Simi Valley, CA) — For nearly four decades, no one knew what was behind the drywall of a closet in Deanie Winter’s Simi Valley home. Not even her own family. Inside the wall—sealed off and long forgotten—were boxes filled with hundreds of books. Each one contained details of a craft technique so original, it once earned a U.S. patent.

That moment of rediscovery didn’t come from a historian or researcher. It came from her grandson. One day, curious about the peeling edge of the closet wall, he looked behind it—and what he found quietly reopened a chapter of Deanie’s life that had been closed for nearly 40 years.

“I had no idea he found them,” Deanie said. “He thought he might be in trouble, so he didn’t say anything. But later, when he heard me talking about putting my book online, he said, ‘You mean those books I found hidden behind the wall?’”

That small moment—an inquisitive grandson, a casual conversation—brought a long-buried dream back to life.

A Craft That Sparked Curiosity

Deanie never set out to invent something. Back in the early 1980s, a friend asked her to help make plant hangers for a retail order. Deanie agreed. It was meant to be a simple side job, but the moment she learned a few basic knots, something inside her clicked.

“I just enjoyed it. I wanted to do more than follow patterns—I wanted to try something no one else was doing,” she said.

Soon, she challenged herself to create the face of a horse using knots. To pull that off, she started experimenting with graph paper and different techniques. But the traditional method she found—Cavandoli knotting—was difficult to use. It required long cords, precise calculations, and a tangled mess of hanging strands. Deanie was determined to find a better way.

And she did.

Reinventing the Art of Macramé

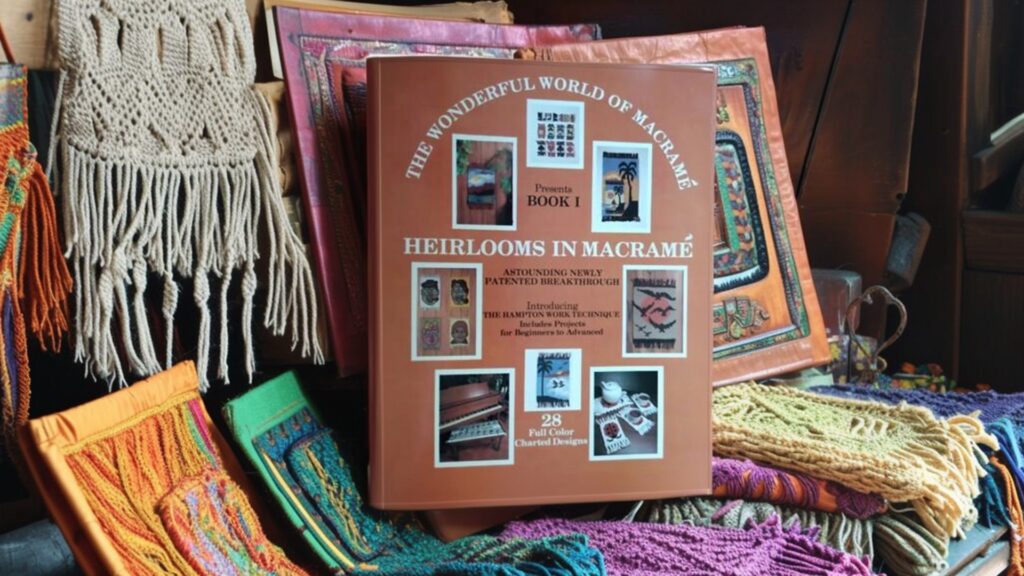

Through trial and error, Deanie created something completely new. Instead of working with long, complicated cords, she developed a system that used short base cords and colored bobbins to build detailed designs. It gave her total control and clarity—making it possible to “draw” with knots, including words, shapes, and even cartoon characters. She called it Hampton Work.

What made Hampton Work special wasn’t just that it was easier to use. It allowed for precise, colorful designs, and left the back of the piece clean—no mess of knots or dangling cords. In a craft that had remained mostly unchanged for centuries, Deanie’s method was a breakthrough.

“I realized no one had ever done it this way before,” she said. “I knew I had something new.”

A Patent Won by Handwritten Letters

Deanie knew she needed to protect her invention. She reached out to a patent attorney, who guided her through the process entirely by mail. They never met in person. She sent in diagrams and handwritten explanations—but when the first submission was denied, her attorney wasn’t eager to try again.

He told her to wait a month or two, until he got back from vacation. But Deanie couldn’t wait.

“I told him to send me everything he submitted, and I’d take care of it myself,” she said.

She rewrote the explanation in her own words, added more detail about how the technique worked, and mailed it off herself. Not long after, the patent was approved.

“When the attorney came back from his trip, he was shocked,” she said. “He said he’d never seen anything like it—that a second submission, done by the client, was approved that quickly. He was amazed.”

From Cross-Country Pitches to a Quiet Rejection

With a patent in hand, Deanie thought her next step would be easy. She reached out to Plaid Enterprises, a major craft book publisher in Georgia. They were interested and invited her to come out and show them her designs in person.

So she packed up her husband and three kids, and the family drove across the country—camping along the way—to pitch her invention.

The meeting went well. Executives at the company were impressed by her ideas, especially when she mentioned pitching to Disney. They told her a contract would be waiting for her by the time she got home.

And it was. But at the end of the contract, she saw something she couldn’t agree to.

“They wanted full rights to the technique. I couldn’t give that up,” she said.

Instead, Deanie decided to publish the book herself. She titled it The Wonderful World of Macramé: Heirlooms in Macramé. Her husband filmed a homemade demo video to show off the Hampton Work method—an ambitious move in the early 1980s. Then they took the book to the Los Angeles Arts & Crafts Trade Show.

There, a Canadian cord distributor offered to buy copies and flew Deanie to Canada to lead workshops. The trip was a success.

But shortly after, life got in the way.

Into the Wall, and Out of Sight

Deanie’s family had to move to Arizona. With the house rented out and nowhere safe to store hundreds of books, she came up with a solution: she boxed them up, sealed them behind drywall in the downstairs closet, and left them behind.

For the next few decades, her focus shifted to raising her family and working in medical billing. Macramé faded into the background. By the time she retired, the idea of starting over felt exhausting.

“I was just too tired of looking at computer screens all day,” she said. “I knew about Amazon, but I didn’t want to deal with all of that.”

The books stayed in the wall. The dream stayed on pause.

A Second Chance

Years later, her son and daughter-in-law moved into the house. That’s when her grandson made his discovery behind the closet wall. Still unsure if he’d get in trouble, he said nothing—until he overheard Deanie talking about the book again.

With help from her daughter-in-law, Deanie finally brought the book back to life. It’s now available on Amazon and eBay.

“I told her I didn’t want any money from it,” Deanie said. “I just want people to know the technique exists. That’s what matters to me now.”

A Name Worth Defending

But not everything has been easy. While shopping at Hobby Lobby recently, Deanie picked up a new macramé book and instantly recognized her technique inside. It had been copied—almost exactly—by a young Canadian author. There was no mention of Hampton Work. No credit at all.

She contacted the UK-based publisher, hoping for acknowledgment. They responded with an offer to mention her as someone who had “done extensive work in DHH knotting” in a future reprint. Deanie declined.

“I told them the name is Hampton Work, and that’s what it should be called,” she said. “That’s what I created.”

Beyond Recognition

Today, Deanie says she doesn’t need the spotlight. What she wants is simple: for people to use the technique, enjoy it, and understand where it came from.

Macramé is seeing a revival, especially in places like Germany and Russia. She hopes Hampton Work can become part of that new wave. And maybe, somewhere down the line, a new generation of artists will take it even further.

She doesn’t have a website. She doesn’t need a brand. She just has her book, her story, and a name worth remembering.

“I know what I created,” Deanie says. “And I know it matters. That’s enough.”